Fighting Yellow Starthistle with Fire and Community

Last week, I participated in my first prescribed burn, an experience that connected me to the land, ancestral fire practices, and a hopeful path toward regeneration. The burn took place in a field near my home, aiming to reduce invasive yellow starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis) and improve ecosystem health.

An Aggressive Invasive

Yellow starthistle, native to Eurasia, likely arrived in California in the mid-1800s through contaminated alfalfa seed. Since then, it has become one of the state’s most aggressive invasive species, thriving in disturbed soils and forming dense monocultures that outcompete native plants, degrade wildlife habitat, and reduce biodiversity. In addition to being harmful to ecosystems, it produces toxins that are especially dangerous to grazing animals, including horses.

Here in Trinity County, it’s everywhere. I spend my summers battling it by hand, pulling up thistle before it flowers while enduring the scratches and painful pokes of its stiff spines. It’s a losing battle at times, and though honeybees love the blossoms, I do not. Fire, when used strategically, can disrupt the plant’s life cycle and deplete its massive seed banks, offering hope for future regeneration.

Applying Fire with Intention

This burn was part of the Yellow Star Thistle Training Exchange (YST TREX), a hands-on program organized by the Watershed Research and Training Center (WRTC), a nonprofit specializing in community-based watershed stewardship. TREX programs are part of a growing movement of Prescribed Burn Associations (PBAs), which are community-based groups that help local landowners, agencies, and tribes safely reintroduce fire onto the landscape. These associations are an important model for building ecological resilience through collaboration and shared stewardship.

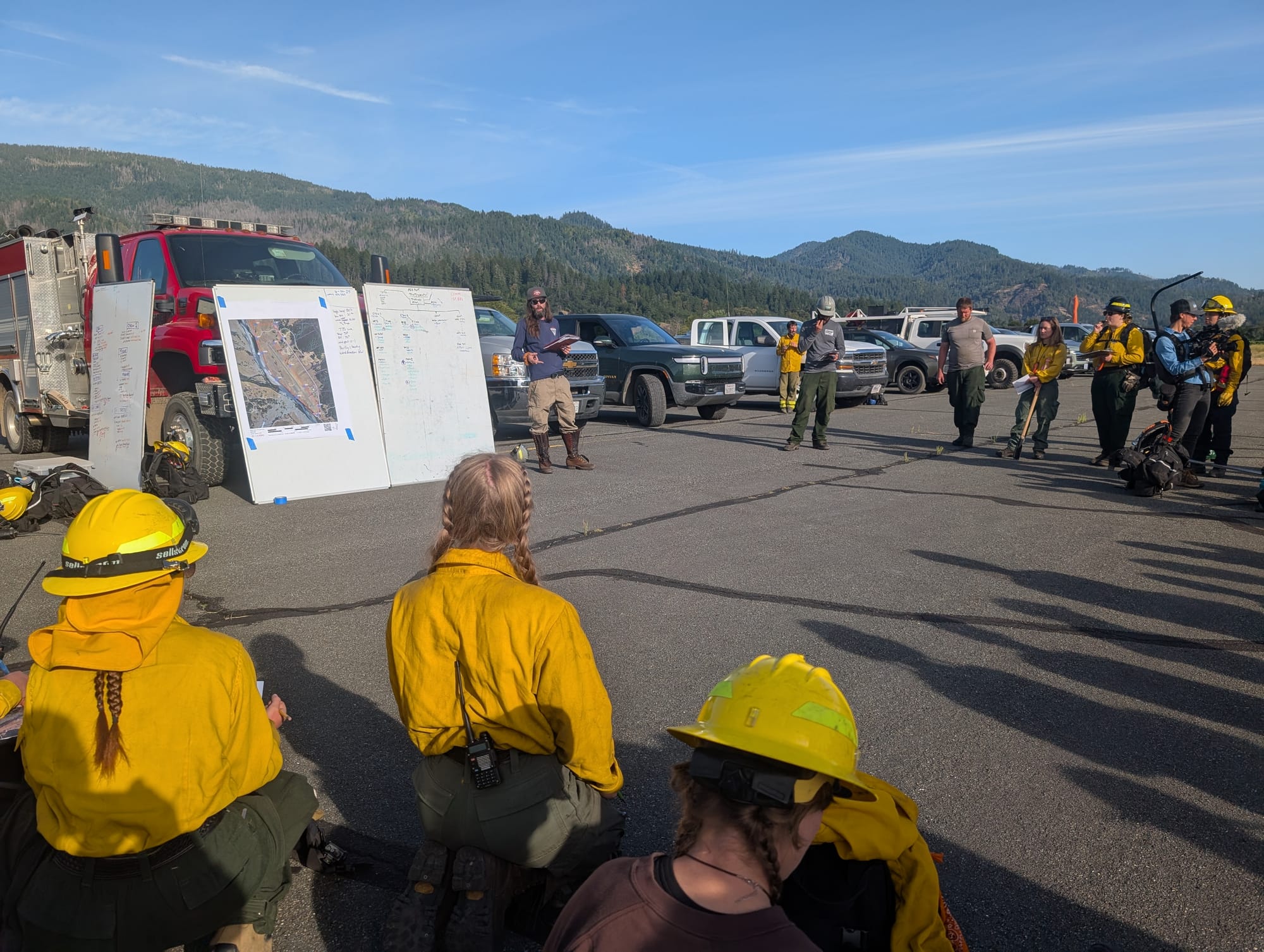

The training brought together more than 50 firefighters, students, and volunteers. It took place on the Hyampom airport in a field of grassland within oak woodlands, on the valley floor. The site functions as an emergency evacuation area and staging ground for firefighting operations during wildfires. Reducing fuel loads here improves ecosystem health and enhances community safety.

The Heat and the Smoke

I was assigned to use a flapper tool, a long-handled implement with a rubber flap designed to smother small flames and direct fire behavior. Paired with a teammate carrying a water pack, I tamped down flames after they were sprayed, helping control the fire’s spread and protect sensitive areas. Our team moved with precision, under the guidance of our unit leader, relying on clear communication and careful coordination. The physical challenge wasn’t the heat, but the thick smoke, which took a toll as I worked steadily through the day, just recovering from a cold. By the end, my clothes were dirty, carrying the scent of smoke, and I was thoroughly exhausted.

Clockwise from top left: Briefing with the Incident Management Team, applying fire to the land and directing its spread, and the immediate results of a successful burn (Liza Welsh, 2025).

The Aftermath and the Recovery

We treated seventeen acres that day. While we didn’t manage to eradicate all the yellow starthistle, we made a significant dent. And knowing that this effort may reduce the plant’s spread next year and help native species return makes it all feel worthwhile. The field, so close to my front door, offers a rare opportunity to observe the transformation over the coming seasons. Few native plant enthusiasts or prescribed fire advocates get to witness such a transformation in real time.

I feel incredibly fortunate to be in this position. I plan to document the recovery of this unit and to stay involved with our local PBA, assisting with future burns. If funding and conditions allow, the unit will be burned twice more over the next two years. After three years of carefully timed fire treatments, the seed bank of yellow starthistle should be mostly depleted, and native species will begin to reclaim the space.

I am grateful for the mentorship, professionalism, and generosity of the entire fire Incident Management Team. Their steady leadership created a safe and welcoming learning environment. I also want to thank our local Volunteer Fire Department. Their participation in this work serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of local knowledge, trust, and teamwork, both in restoration and in emergency response.

This burn was more than a day of work. It was an invitation to care more deeply, to listen, to learn, and to take part in tending the land with intention.

If you're passionate about land stewardship, fire ecology, or community-based restoration, I encourage you to get involved with your local Prescribed Burn Association (PBA) or with other ecological restoration initiatives. Together, we can make a lasting impact!

Explore Further Want to dive deeper into the tools, seeds, and systems mentioned in this post?

Let's continue the conversation about how we can nurture healthier ecosystems and stronger communities.

🌍 Visit my website lizawel.sh to learn more about me and my work.

💬 Want to connect? Follow @seedsandsystems on Instagram or Bluesky.

✉️ Subscribe for posts delivered directly to your inbox.

🔄 Enjoyed the post? Use the buttons up top to share it with others who might find it valuable!